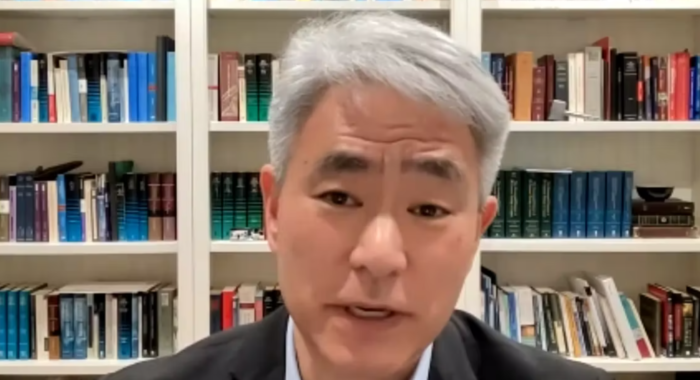

Richard Mouw is professor of faith and public life and president emeritus of Fuller Theological Seminary. He served as the seminary’s president for 20 years. Prior to teaching and leadership at Fuller, he taught at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, for 17 years. He has participated on many councils and boards, recently serving as president of the Association of Theological Schools. Mouw has written 19 books, including “Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World.”

Kindness and gentleness should be especially characteristic of those of us who are Christians. We were created for kind and gentle living. Indeed, kindness and gentleness are two of the fruit-of-the-Spirit characteristics that the apostle Paul mentions in Galatians 5. When Christians fail to measure up to the standards of kindness and gentleness, we are not the people God meant us to be.

Not Civility Alone

Not that civility is the be-all and end-all of life. We will not solve all our problems simply by becoming more civil people. There are times when it is appropriate to manifest some very uncivil feelings. “Passionate intensity” is not always out of place. If I am going to be a more civil person, it cannot be because I have learned to ignore my convictions. As Martin Marty has observed, one of the real problems in modern life is that the people who are good at being civil often lack strong convictions, and people who have strong convictions often lack civility. I like that way of stating the issue. We need to find a way of combining a civil outlook with a “passionate intensity” about our convictions. The real challenge is to come up with a convicted civility.

“Inner” Civility

Civility is public politeness. It means that we display tact, moderation, refinement and good manners toward people who are different from us. It isn’t enough, though, to make an outward show of politeness. Being civil has an “inner” side as well. To be sure, for some people civility is only a form of playacting. Many people today think of civility as nothing more than an outward, often hypocritical shell. But this cynical understanding of civility is yet another sign of the decline of real civility. In the past civility was understood in much richer terms. To be civil was to genuinely care about the larger society. It required a heartfelt commitment to your fellow citizens. It was a willingness to promote the well-being of people who were very different, including people who seriously disagreed with you on important matters. Civility wasn’t merely an external show of politeness. It included an inner politeness as well.

Flourishing in Humanness

To be good citizens, we must learn to move beyond relationships that are based exclusively on familiarity and intimacy. We must learn how to behave among strangers, to treat people with courtesy not because we know them, but simply because we see them as human beings like ourselves. When we learn the skills of citizenship, Aristotle taught, we have begun to flourish in our humanness. Acorns do not realize their innate possibilities until they grow branches and sprout leaves. And people do not attain their full potential until they learn how to behave in the public square.

The Struggle for Civility

But how can we hold onto strongly felt convictions while still nurturing a spirit that is authentically kind and gentle? Is it possible to keep these things together? The answer is that it is not impossible — but it isn’t easy. Convicted civility is something we have to work at. We have to work at it, because both sides of the equation are very important. Civility is important. And so is conviction.

The Bible itself recognizes the difficulty of maintaining convicted civility. The writer of the epistle to the Hebrews lays the struggle out very clearly: we must “pursue peace with everyone,” he tells us, while we work at the same time to cultivate that “holiness without which no one will see the Lord” (Hebrews 12:14).

For some of us, “pursuit” is a very appropriate image. Civility is an elusive goal. We have to chase after it, and the chasing seems never to end. We think we have finally caught it — and then civility slips from our grasp again. Just when we think we have figured out how we’re going to live with the latest cult or how to tolerate the most recent public display of sexual “freedom,” someone seems to up the ante; and the limits of our patience are tested all over again. So the pursuit goes on and on.

Promoting the Cause

There are two obvious ways to produce more people who combine strong convictions with a civil spirit: either we will have to help some civil people to become more convicted, or we will have to work at getting some convicted people to become more civil. Or both, since each of these strategies is important.

The first requires a kind of evangelism. We need to work at inviting the “nice” people in our society to ground their lives in robust convictions about the meaning of the gospel. But in order to do that, we have to be sure that we are doing our best to present discipleship as an attractive pattern of life.

This means that we must also devote our energies to the second strategy: learning as Christians to be a gentler and more respectful people. I admit that trying to make believers gentler and more “tolerant” will strike some Christians as wrong-headed. What about the devout, passionate people who picket abortion clinics and organize boycotts against offensive television programs?

They might worry that becoming civil will mean a weakening of their faith. I am convinced that this is not necessarily so. Developing a convicted civility can help us become more mature Christians. Cultivating civility can make strong Christian convictions even stronger.

Richard Mouw writes wisely and helpfully about what Christians can appreciate about pluralism, the theological basis for civility and how we can communicate with people who disagree with us on the issues that matter most. This excerpt from “Uncommon Decency” © 2010 by Richard J. Mouw is used with permission of InterVarsity Press. Order at IVPress.com.

View All Articles

View All Articles