When the National Association of Evangelicals was formed, it appeared at the time to be an unlikely association of Christians. The Statement of Faith reached its final form in 1943 in a gathering of more than 1,000 attendees from almost 50 diverse denominations and traditions, including Baptists, Presbyterians, Wesleyans, Pentecostals, Congregationalists, Dispensationalists and Anabaptists.

Many were emerging from an era of separatism in which efforts at unity were minimal and even discredited. But, attendees at the Chicago event noted a unique moving of the Holy Spirit. Thus, “Adopted — without dissent — was a seven-point doctrinal affirmation that would not only be NAE’s standard, but it also became the official statement of faith for many … evangelical organizations in the years which followed,” according to Arthur H. Matthews in his book, “Standing Up, Standing Together.”

The NAE intentionally did not copyright its Statement of Faith, so that it would be used widely. As a result, countless evangelical groups and organizations across America and around the world have adopted the NAE statement as their own. Some Christian colleges and seminaries require incoming students to sign it, establishing shared faith among students.

Harold John Ockenga, the first NAE president and eventual first president of both Fuller Theological Seminary and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, gave the clarion call in the opening address of the movement: “The hour calls for a united front for evangelical action.” There was an emerging call for unity among evangelicals, who to this point had been largely working in isolation from each other. Making an impact for the cause of Christ in a troubled world called for new synergies.

But how could such a diverse body of evangelicals come together? The early pioneers of the NAE focused on the core essentials of Christian faith, laying aside differences over ecclesiology, ordinances (or sacraments), eschatology and other doctrines deemed to be secondary in nature. They sought to find a path between the Social Creed (1908) of the Federal Council of Churches (which in 1950 became the National Council of Churches), and the more strident, separatist stance of the American Council of Christian Churches led by Carl McIntire. As Elizabeth Evans notes in “The Wright Vision: The Story of the New England Fellowship,” “These evangelicals agreed on the essentials of the faith, even though they had quite different views on nonessential matters.”

The seven-point NAE Statement of Faith is fairly straightforward:

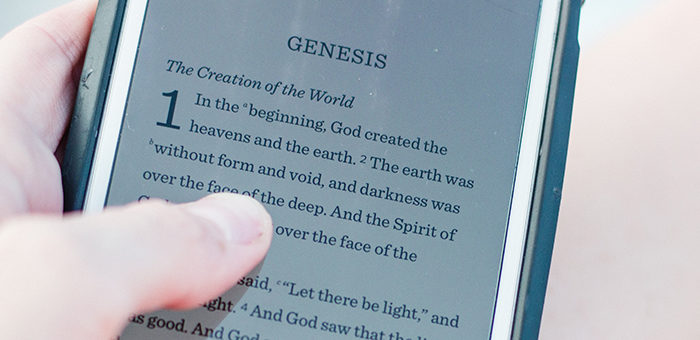

- We believe the Bible to be the inspired, the only infallible, authoritative Word of God.

- We believe that there is one God, eternally existent in three persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

- We believe in the deity of our Lord Jesus Christ, in His virgin birth, in His sinless life, in His miracles, in His vicarious and atoning death through His shed blood, in His bodily resurrection, in His ascension to the right hand of the Father, and in His personal return in power and glory.

- We believe that for the salvation of lost and sinful people, regeneration by the Holy Spirit is absolutely essential.

- We believe in the present ministry of the Holy Spirit by whose indwelling the Christian is enabled to live a godly life.

- We believe in the resurrection of both the saved and the lost; they that are saved unto the resurrection of life and they that are lost unto the resurrection of damnation.

- We believe in the spiritual unity of believers in our Lord Jesus Christ.

This statement has become the primary qualification for membership in the NAE. Its broad-strokes orthodoxy has enabled it to be used widely by denominations, educational institutions and evangelical organizations.

As NAE President Leith Anderson notes:

It says a lot in very few words. And, there is much it does not say. There are distinctives among our member denominations that vary in understanding what the Bible says about prophecy, spiritual gifts, church government and more. The NAE Statement of Faith was never intended to speak to every doctrine or teaching but to establish the center that all evangelicals share. Long before the notion of defining organizations by their center rather than their boundaries, the NAE strongly declared the center of our faith in the Bible and in Jesus Christ.

While the NAE Statement of Faith was a significant factor in bringing evangelicals together 75 years ago and continues to serve the evangelical community well, many of us have noted one missing element in the statement: the Church. The absence of any reference to the Church likely reflects the individualism of the time, as well as the antipathy to the conciliar movements such as the World Council of Churches or National Council of Churches, with their focus on structural unity over theological and spiritual unity. If the statement were written today, I suspect that there would be a clause in point seven or a separate point eight, reminding us that to be a believer in Christ is to be in the Body of Christ, his Church.

Nevertheless, the statement itself serves as a connector for people of shared faith and inspires us to work as the Body of Christ in united action for his glory.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

Dennis Hollinger is president and the Colman M. Mockler Distinguished Professor of Christian Ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, Massachusetts. Previously, he served as president and professor of Christian ethics at Evangelical Theological Seminary in Myerstown, Pennsylvania. Hollinger received a B.A. from Elizabethtown College, an M.Div. from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, an M.Phil. and Ph.D. from Drew University, and did post-doctoral studies at Oxford University.

View All Articles

View All Articles