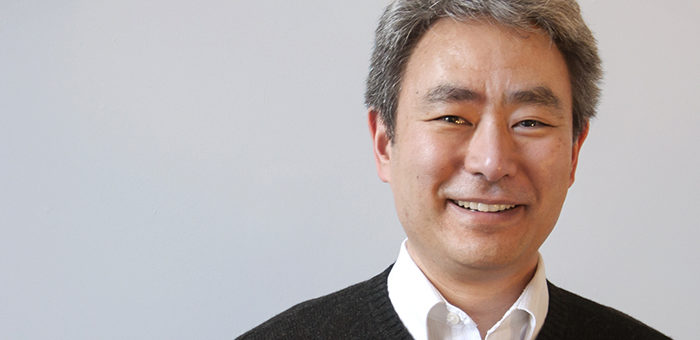

Mark Noll is an emeritus professor of history from both Wheaton College and the University of Notre Dame. He is the author of “Protestantism: A Very Short Introduction,” “America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln,” “God and Race in American Politics: A Short History,” and “The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind.” Noll is also co-editor of “Evangelicals and Science in Historical Perspective” and “B. B. Warfield: Evolution, Science, and Scripture.” He holds degrees from Wheaton College, University of Iowa, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and Vanderbilt University.

The word “evangelical” seems to be in trouble — but for two different reasons. In the rough and tumble world of American politics, the label is now often used simply for the most active religious supporters of President Donald Trump. By contrast, in the rarified world of professional scholarship, academics now sometimes treat it as a term with so much ambiguity, fluidity and imprecision that it cannot meaningful designate any single group of Christians.

For both of these contemporary opinions, there are some admittedly good reasons. Yet stepping back for a longer view historically and a wider view internationally opens up another possibility: Maybe the scholars are too fussy, and the pundits too shortsighted.

More Than Right Wing

In the media’s obsession with partisan politics, evangelicals are the white conservative voters who provide overwhelming support for the nationalistic populism of Donald Trump. A big recent book by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Frances Fitzgerald presents this narrative in carefully researched detail. The book, entitled “The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America,” devotes three-fourths of its over 600 pages to the white Christian Right, implying that this emphasis captures the essence of evangelicalism.

Yet if this identification makes considerable sense, its limitations are just as obvious. In a careful review of Fitzgerald’s book in Christian Century, Randall Balmer of Dartmouth College observes that in some past eras, evangelicals included as many social progressives as conservatives. Before the Civil War, the nation’s best-known evangelist, Charles Finney, and several of his converts like Theodore Dwight Weld, actively opposed slavery. After the Civil War, the firmly evangelical Frances Willard guided the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in its fight to protect women and children from abuses fueled by alcohol. Even in the recent past, international efforts for peace in the Middle East were led by Jimmy Carter, a Southern Baptist Sunday School teacher.

Observers like Balmer do not deny that evangelicals have often contributed substantially to conservative political causes, but they are certainly correct that throughout American history “evangelical” has always meant more than the right wing.

Beyond Bebbington

The conceptual challenge from scholars poses a more basic challenge than the simplistic equation of evangelicalism and right-wing politics. In 1989 the British historian David Bebbington provided a succinct definition in his book, “Evangelicalism in Modern Britain,” that has been widely referenced. That definition identifies evangelicalism as a form of Protestantism with four distinct emphases:

- conversion, or “the belief that lives need to be changed”;

- the Bible, or “the belief that all spiritual truth is to be found in its pages”;

- activism, or the dedication of all believers, especially the laity, to lives of service for God, especially in sharing the Christian message far and near; and

- crucicentrism, or the conviction that Christ’s death on the cross provided atonement for sin and reconciliation between sinful humanity and a holy God.

While many have employed this definition to good effect, others have pointed out difficulties. Most obvious in an American context are divisions created by race. Along with many white Protestant groups that have embraced these four characteristics, so have many African Americans. Yet the American reality of slavery, followed by culturally enforced segregation, means that whites and blacks who share these religious emphases share very little else, as Michael O. Emerson and Christian Smith demonstrated in “Divided by Faith.” An evangelicalism that includes both blacks and whites might make sense in very narrow religious terms, but far less in the actual outworking of American history.

A broader historical challenge has recently come from Linford Fisher of Brown University in the substantial article “Evangelicals and Unevangelicals,” published in Religion and American Culture, which argues that “evangelical” has often meant less, and sometimes more, than the Bebbington definition. From the time of the Reformation and for several centuries, the word usually meant simply “Protestant” or, almost as frequently, “anti-Catholic.” During the 18th century revivals associated with George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, and the Wesleys, “awakened” believers in Britain and America did not use the word too frequently. When they did, it meant “true” or “real” religion as opposed to only formal religious adherence.

Linford then documents the way that after World War II, former fundamentalists embraced the word as they sought a less combative, more irenic term to describe their orthodox theology and their desire to re-engage with society. Organizations like the National Association of Evangelicals and the wide-ranging activities of Billy Graham popularized the word. In the process some Pentecostals, Lutherans, Mennonites, Christian Reformed and others who had not been associated with the main body of America’s earlier “evangelical Protestants” were now glad to join in using it to describe themselves. At the same time, other Protestants who had thought of themselves as evangelicals began to avoid the word as designating something too close to fundamentalism.

Evangelicals Around the World

Those who raise their sights to the world at large add more complexity. All careful scholars now find more evangelicals, however defined, outside of Europe and North America than in these former evangelical homelands. A full recent survey by Mark Hutchinson and John Wolffe, “A Short History of Global Evangelicalism,” and a new reference volume edited by Brian Stiller, “Evangelicals Around the World,” both describe an increasingly diverse worldwide network. Yet it remains a network linked by common religious convictions. Together they indicate that the politics and preoccupations of the American media should not be allowed to dictate what “evangelical” means.

A recently published study by Australian scholar Geoff Treloar, “The Disruption of Evangelicalism,” brings to a conclusion a five-volume history of evangelicalism in the English-speaking world that I have been privileged to edit with David Bebbington. These five volumes, published by InterVarsity Press, carry a coherent story from the early 1700s through the 20th century. It is coherent, however, not because all of the many individuals and organizations identified as evangelicals stood shoulder to shoulder on all questions of Christian belief and practice.

Instead, the books find it an easy matter to document multiple connections descending historically from the Great Awakening and the Evangelical Revival of the 18th century. They also document a clear historical trajectory marked by serious commitment to the authority of Scripture, the saving work of Christ’s death and resurrection, the possibility of lives revived and redirected by the converting power of the Holy Spirit, and the necessity for all believers to put their private faith into public action.

To put it differently, the books hang together because they record the history of English-speaking Protestant Christians who have defined themselves by their attention to the same foundational questions that George Whitefield and John Wesley addressed in their day.

A Term for Today

This approach to a broad history over a long period of time turns out to be helpful for narrow American issues in the very recent past. Yet some are still thoroughly disillusioned and, though once recognized as evangelicals, now are giving up on the term.

But others say, “not so fast.” In an online article at Faith & Leadership, Molly Worthen of the University of North Carolina insists that “evangelical” remains a viable term when considered as a “shared conversation” about how to reconcile faith and reason, what true salvation means, and how private faith relates to modern secular life. In turn, Worthen concludes about the contemporary United States that “the religious right is really the product of a civil war within evangelicalism. It represents the political efforts of a fairly narrow slice out of the myriad evangelical traditions that have been active in American and Western history.”

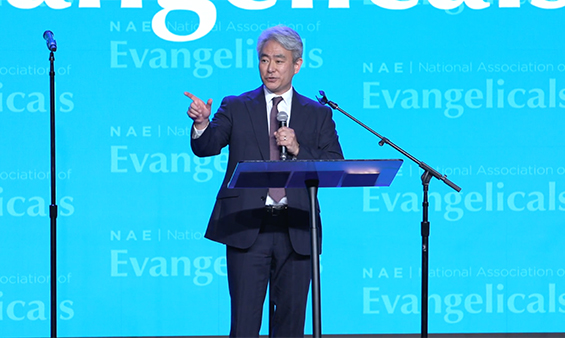

Considered from this perspective, “evangelical” and “evangelicalism” do remain flexible terms. Yet when individuals or organizations define their use of the terms carefully, they are not so flexible as to become meaningless. The website of the National Association of Evangelicals is one of the best places to view such clarifying specificity. It positions the terms against the background of a shared history and fleshes them out in specific affirmations about the Bible, Christ’s saving work, Christian activity, and the converting power of the Holy Spirit. It shows that the NAE, together with the tradition it represents, is not a tool of political partisanship, but a set of believers with a definite Christian stance.

Our world of rapid change and media rush-to-judgment threatens to destabilize all matters that once seemed fixed and secure. Yet for the terms “evangelical” and “evangelicalism,” ambiguity is not the only possibility. When used with responsible attention to history and careful focus on generally accepted norms of the Bebbington definition, they can still communicate reality and not just confusion.

This article originally appeared in Evangelicals magazine.

View All Articles

View All Articles